Chapter Twelve: Sands Home

The next summer and those that followed were spent in a more comfortable apartment at Sands Home, a sprawling two-story building that had been occupied by retired British soldiers and now housed the families of missionaries. Our family grew unusually intimate, living and sleeping in one big square room, parents on a double rope-woven charpai, we children in bunks. A fireplace with a mantel where caught moths and tarantulas died slow deaths in killing jars heated the room with wood bought from wood wallahs or pine cones collected by us children for five annas a bag. An enclosed porch served as a living and dining room, its many windows allowing Mother to keep an eye on us children playing ring toss or badminton in the adjoining courtyard. I don’t remember the kitchen but the bathroom with its pull-chain toilet, wash basin and oval tin tub filled with water heated on the kitchen stove inspired apocryphal stories probably cooked up by my dad, including the one about the python entering through the drain hole in the outside wall, sliding around the tub containing my astonished mother, and, with a wink, slipping back out. Except for the wink, which I suspected Dad added for effect, I believed this story into my seventies, until mother assured me it was fiction.

“The Hills” gave me time with my Dad I never got in Lahore. Although sometimes called upon to deliver someone’s baby on a kitchen table, attend the sad “clinic” that each morning appeared at a respectful remove from our door, or even sew up his own hand when he cut it opening a tin of powdered milk, nevertheless had time to kill when he came to see us in Murree. A restless man, he soon was cheering his family along woodsy trails, taking pictures, pointing out plants and wildlife, or teaching us silly camp songs he learned during his youthful summers in Michigan.

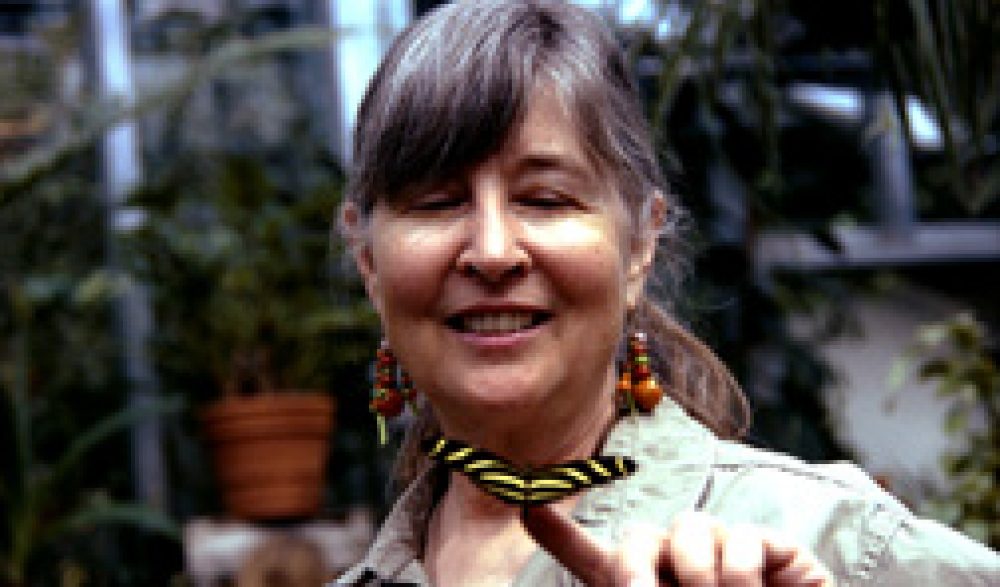

But what he loved most was butterflies. My father shared his lifelong love of lepidoptera with the joy of a boy skipping school, and I took to it with a consuming passion that proved me my father’s daughter. What enthralled me, after the precious time I spent with my dad, wasn’t so much the butterflies as the process of their collection: the preparation, stalking, catching, preserving and displaying. I fell in love with the hunt: the lurch my body took when my eyes flicked onto a rare pair of wings, the focus of a chase more compelling than fiction, the shouts of triumph after so many misses, the sorting, arranging and identifying, the small distinctions, the tiny but significant details.

My father lavished the particular care to butterflies he was reputed to take with his patients. The whole family made our equipment. My mother hemmed white net bags that we children slipped onto coat hangers Dad forced from triangles to loops and fastened with medical adhesive tape to the severed ends of broomsticks. Dad covered granules of potassium cyanide with cotton, then plaster of Paris (later cast around my brother’s broken arm), pouring inches into our lethal glass “killing jars”.

We took to the woods and meadows, waving our nets like flags, sneaking up on bushes like tigers, tensing, swooping, then breathlessly checking to see if we “Got it!” Softly, from the outside of the net, pinching with my left hand the slim, trembling thorax and shutting the beating wings, I caught the halved creature between the forefinger and thumb of my right hand, carefully, so not to smudge the black-and-turquoise iridescence of a swallowtail or the scarlet freckles of a tangerine skipper no bigger than a bee. My delicate catch did not die in a crow’s black beak or wrapped in a chameleon’s sticky tongue. A small girl, not to be found a sissy, reluctantly but firmly pressed out its little life, dropping it in the killing jar, screwing on the lid, leaving it there until she was sure it was dead.

With butterflies, that time was mercifully short—five minutes, perhaps, or ten. Moths, too fat to be pinched unconscious, died slower deaths—hours, sometimes days. I did not like the moths, their bulging bodies, hairy as rodents, too big to be bugs, their wardrobe unappealing and drab. Dad seemed to love them though, as if they proved the dark miraculous. He caught the moths at night, as they beat like hands against our screens, or he painted molasses on the trunks of trees, where lunas, sphinxes, huge brown cecropias and suede-like polyphemus moths got stuck in his sweet lures.

Quickly, before our butterflies stiffened, we took them indoors and closed the windows, lest a stray breeze blow the feathery wings off the table. We laid each specimen “belly-up” on a cork board and “stretched” it into a show-off pose, anchoring the wings with thin black pins and half-inch strips cut from index cards. After a few days, we arranged our prizes, now thoroughly dried, on milkweed fluff we’d gathered ourselves, or surgical batting from the hospital, then enclosed them under black-framed glass. A dozen of these cases, big as trays, inhabitants intact and only slightly paled, into my fifties filled a wall over my bed.

I couldn’t kill a butterfly now, but the collection bug bit hard. I learned to spot leaflike chrysalises camouflaged in boughs of trees and shrubs, and monarchs’ translucent jade cups hanging behind the leathery milkweed leaves. I gathered these like fruit and brought them home, along with silken moth cocoons, arranging them on the window sill and checking each morning to see what might have emerged: a yellow swallowtail, perhaps, or a black and orange monarch, a spotted wood nymph, or the narrow gray wings of a hawk moth. I gathered caterpillars in shoeboxes, lady bugs in jars, fireflies in the sphere of my cupped hands, pinecones in burlap bags recently emptied of walnuts. When I turned nine, my father, recognizing in me a clear inheritance, gave me his boyhood stamp collection, to which throughout my youth I made many colorful additions soaked from the remains of his voluminous international and Pakistani mail, or ordered from the tiny ads in the backs of magazines.

In the decades since childhood I have been on the prowl, eyes peeled for it didn’t matter much what—wildflowers, striped fabrics, egg cups, unusual fruits. I discovered early that nothing is what it seems, nor will I really see it—whether butterfly, lake, button, or book—until I have arranged it out of context with others of its kind. The proximity of similar objects, ideas, even memories, lifted from their comfortable habitats never fails to reveal to me distinctions too subtle for me before. Patterns emerge as I re-sort a collection again and again, like playing cards: by size, color, shape, degree of beauty.

Now, writing of my life, I treasure hunt within, spy on myself, like a surgeon who knows the shape and color of what we carry but which most of us have never actually seen. I, who thought I knew myself after years of Freudian, Gestalt and Jungian therapies, explore the body of my life and find I have much to learn. Memories merge into specialized museums: lovers, fruits, books written, books read, risks taken, loved and hated shoes, entomological encounters, hairdos, bedrooms, fears, wounds, flowers, havens, trees, meals, scents. Patterns emerge, shaping my several careers, two marriages, motherhood and, despite frequent unwelcome outcomes, my irascible susceptibility to enchantment.