My mother wasn’t the only adult in our cool, safe house who could who could charm us with stories. Frieda Enss, another of my mother’s older sisters, had accompanied us to Pakistan to administrate the new United Christian Hospital in Lahore, but I suspect she also may have come to keep an eye on my mother—the Enss sisters brooked no threats to one another.

There was a strong family resemblance: Aunt Fritzi was tall and large-boned like my mother, but her hair was black and straight, not chestnut and wavy, and her eyes, unlike my mother’s cool blue, were the color of my mother’s hair. Like her sister, Aunt Fritzi got what she wanted, usually on her terms. Hardworking, righteous, fair to a fault, she frightened people with her stem insistence on working harder than anybody else. She never married and if she ever had a beau, she kept him a secret from me. And although she was not thought beautiful, as Mother was, she seemed to be regarded with as much respect as a man, important as an authority in a culture where most women, publicly shrouded under voluminous black or white burkas, moved through the bazaar at least in pairs and as if—I’d speculate when failing to glimpse their feet—on wheels.

However, Aunt Fritzi had a silly side one had to see to believe. Although her apartment was close to the hospital, she often dined at our house. On lucky nights, when the adults’ dinner had not yet been served and we children had retired, she would appear at our bedroom door and wave her hand, like a queen flinging coins to her subjects, filling the room with what she referred to as “fairy dust”. “What do you want to hear about tonight?” she’d ask, always letting us choose our story and perching on a bed.

“The Keyhole Fairy!” or “the Swiss Cheese Fairy!” we’d shout, making it as hard for her as we could.

Nothing, however, could stump Aunt Fritzi. Hooting with laughter at her own nonsense, she’d tell as wild a tale as ever we’d read in a book. When she got stuck, she’d fish: “And what do you think happened THEN?” Aunt Fritzi would ask, dramatically, leaning forward, playing for time. Perhaps the problem was to extricate the Dragonfly Fairy who’d been caught in the beak of a parrot.

“She got SWALLOWED!” I’d cry, “like Jonah and the whale.”

“NO!” Aunt Fritzi’d say smugly. “That’s not what happened.”

“The parrot bonked himself on a tree and dropped her!” Dewey might suggest.

“NO again!” Aunt Fritzi would declare, grinning dangerously.

We always guessed wrong, but something would save the fairy. Something always did—Aunt Fritzi made bold and unapologetic use of deux ex machina. While we exhausted ourselves with endings, Aunt Fritzi was thinking. Suddenly her eyes would brighten and she’d interrupt: “NO, children, you haven’t guessed it, but you’re close! Listen carefully! A storm cloud blew up just in time! ‘Ka-SMACK! Ka-CRASH! KA-BOOM!’ went the cloud and startled three green feathers right out of the parrot’s tail!”

“’Yike!’ yelled the parrot as the feathers blew away, and when the parrot yelled, its big red beak opened and the Dragonfly Fairy flew free.” We’d cheer, at the end, vastly relieved at the rescue of the protagonist who in short order had become beloved. Aunt Fritzi was relieved, too, for having thought of an ending just in the nick of time. She’d fall back on the bed, gasping with laughter at her own chutzpah.

“So how come the parrot didn’t catch her again?” I might have demanded, not wanting the evening to end.

“Oh, well that’s easy. Anybody ought to know THAT!” Aunt Fritzi would say in a superior tone, pausing again for apparent effect as she frantically wracked her brain. “Dragonflies can fly backward and parrots can’t!” I doubt I’d have pushed that farther. You could push Aunt Fritzi just so far before she’d fold her arms and drill you with her brown-black eyes.

The only other times I heard Aunt Fritzi laugh like that, shriek, actually, uncontrollably, was with my mother, and the only time I ever heard my mother laugh from her gut, actually giggle and hoot, was with Aunt Fritzi, or, later, on rare occasions, with one or more of her other sisters. Three Enss sisters in the same room could charge admission. I never understood this instant rapport between these eccentric, long-separated siblings, and I don’t remember my mother seeming particularly depressed or unhappy when I was young. However, the only times I’ve observed her “letting down her hair,” as she and Aunt Fritzi called these occasions, was in her sisters’ company.

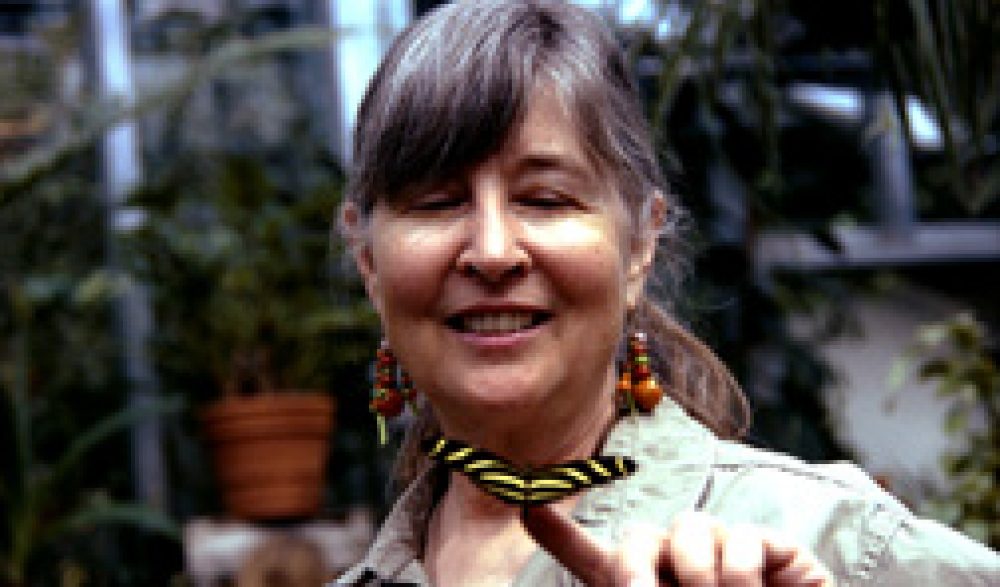

When Aunt Fritzi was eighty-two and reluctantly retired from her administrative career, I urged her to write down her fairy tales, or at least let me record them, but she said she couldn’t remember those stories any more. I have inherited part of her whimsy: With time and solitude, I can rhyme a yarn silly enough to regale any four-year-old, and I have read my children’s books to hundreds of school kids with all-out Fritzi panache. But her gift of spinning a story from fairy dust continues to elude me.

MEMOIR WORKSHOP: I’m on a roll, people! Apparently I write best when my plate runneth over. I have suddenly found myself working on three books at once: my memoir, a new edition of Great Lakes Nature for Indiana University Press, plus major work on my mother’s memoir that I thought was finished. For some reason I don’t understand, the pressure appears to have oiled the word works. I also thank you for your kind and interesting responses and your own memories that mine have inspired.