I learned early that paradise has a down side, for I led a solitary life for a child. Girls were not allowed to play but were put to work at an early age, often collecting cowpies to mix with straw for fuel, slapping them to dry against the mud walls of their homes. I was often left to spy from behind the kitchen garden hedge on my brother Dewey, a year-and-a-half younger than myself, who had become skilled at marbles. Dewey and two of Annie’s and David’s sons, Edwin and Patrick, would gouge a small hole in the hard-packed road and whack each other’s marbles, not by scooting them over the ground, but by drawing one back against a third finger and letting it fly like a bullet. (The tendon in Dewey‘s shooting finger became so stressed that twenty years later it required a surgical repair.) They’d play marbles for hours, chattering so fast in Urdu, I couldn’t tell who was talking,

I wished I could speak Urdu like that, but I was not included in my brother’s games or in the arduous semi-weekly lessons both my parents endured from the severe, graying man in the maroon fez and white chemise and pants. Their text was a worn fat book with blue fabric covers and pages as thin as a Bible’s, across which black ink splattered in strange arcs and dots, backwards. That much I knew: Urdu read from right to left, the book from back to front. My father, whose pronunciation sounded bad even to me, took to Urdu like a duck in a bathtub, speaking with ludicrous enthusiasm. The Pakistanis loved it and his willingness to risk making the most out of whatever little he actually knew often saved him the nuisance of translators and freed him to be his fast-paced, extroverted self.

My mother became a reluctant user of Urdu, although she didn’t seem to need it. A born administrator, she had only to exude what she wanted and magically, it seemed to me, it was done. Her complex household projected a cool, hushed calm nothing short of a miracle and provided a safe oasis from which I could adventure into the rich world of our own back yard, and, from there, on my bicycle, beyond. Not until her sixties, when she taught music to children in the British Virgin Islands, later developing an ambitious musical program and choir for her retirement community, would my mother apply her ample abilities in so many satisfying directions. The apparent detour from what I imagine might have been her ambitions may well have become their fulfillment.

I found my companions in books. In my mother’s house I fell under the spell of words: first those I learned to read, then words read aloud, spun on the spot and recited. The alphabet became the DNA from which I could invent a new world faster than God. Although my mother was not herself verbally facile—she seemed to me to use words like bricks, examining each choice before its cautious alignment with its predecessor—she valued culture, education and, above all else, creativity. With a little help from my Aunt Frieda and my dad, I was presented with a verbal carnival.

Back in Chicago, before we had left for Pakistan, my mother had set about solving the problem of how she would educate three children for five years in a place without an English-speaking school. None of the usual solutions met her approval: She dismissed the Calvert home study program as dull; Woodstock, the boarding school in India where the other “Europeans” (as we often were called) sent their kids, was too distant and dangerous. In the end, she chose to teach us herself, despite the fact that, having majored in choir directing and lacking a college degree, she must have felt ill-prepared..

Never flumoxed for long, my mother did as she has often done when presented with a worrisome problem: She sought out an authority. She consulted the head of curriculum for the Chicago public schools, a woman named Mrs. Bozwinkle. I doubt I ever met Mrs. Bozwinkle, but I was sure I knew what she looked like: an imposing, large-bosomed woman with a preference for unfashionably bright garments and chunky jewelry, professionally assured, personally wise, who, unlike Jehovah, saw me and approved. As though reading my heart, Mrs. Bozwinkle saw to it that our missionary barrels contained, in addition to readers and texts, picture books and novels that cradled my sanity through five frequently lonely years.

Our school room, located at the opposite end of the house from my parents’ bedroom, was crammed with books. They occupied an entire wall, ceiling to floor and I read them all, several times. I raided neighbors’ bookshelves for Greek myths and fairy tales. I can’t remember ever not knowing how to read. Dick and Jane, Spot and Puff number among the hundreds of characters who, in my own good time and only at my say-so, entered the magic circle of my secret inner life. Heidi, Brer Rabbit, Mowgli, Jo, Diana, and Persephone, may never have set foot on this earth, but they rarely failed to enchant me, loyal friends who lured me into their landscapes, accepted my projections, granted my wishes and sometimes broke my heart. But they never abandoned me, lied, or broke their promises. They loved me like the cat or dog I wasn’t allowed to have, demanding nothing more than my attention.

For the rest of my life, a book would be splayed within reach—by my bed, desk, or toilet; on a chair, sofa, or the passenger seat of my car; or tucked in my purse, the place marked by whatever was handy so that, at the least excuse, I could re-enter its safe, unpredictable world. A Carnegie-size library could barely house the books I have absorbed in my seventy-year reading career, but I carry them all, and, should there be a life after this one, will take every one of them with me.

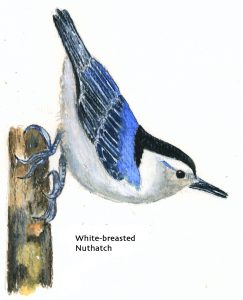

MEMOIR WORKSHOP NOTE: I apologize for having abandoned my memoir for so many weeks—I seem to have lost my once-impressive ability to multitask. While not writing, I completed a set of 24 watercolor pencil nature drawings for my new line of note cards. (Check them out in my Etsy store: beaverislandarts.etsy.com. Please!) I even finished editing my 97-year-old mother’s just-completed second memoir (Read my above chapter if you don’t believe she’s still writing!) I have to say, it’s pretty embarrassing to have my procrastinations witnessed by so many of you. But no more excuses! I’ll be back!