Our family arrived in Lahore just two years after the horrific and bloody 1947 Partition during which over a million people died as Muslims, leaving India for Pakistan, and Hindus and Sikhs, fleeing Pakistan for India, clashed. After a period of sectarian violence said to be worse than the Nazi death camps, things in Lahore began to settle. For the nearly five years that we lived there, I found our large compound—home to Forman Christian College, United Christian Hospital and their associated students and staff—an oasis so peaceful that, until the end, I was oblivious to chaos. While my father spent twelve hours or more a day attending to desperate medical needs, Mother took charge of our social life, a delicate task involving missionary families from “The States,” Pakistani families who might come to dinner and the British.

As we children were rarely included in the world of adults—in Lahore we were usually fed by servants and put to bed before the grown-ups dined—I can only assume that my mother, placing high value on acceptable behavior and schooled by the experienced and always generous Theresa Vroon, overcame the local cultural challenges with a minimum of offense. And if the remnants of the British, who though booted out of power still hung around, were snooty, my mother could out-snoot them, equipped by my Sheffield-born grandmother with sufficient etiquette to dine with the queen, skills my mother wasted no time passing along to me. When I’d question how the placement of four forks, two knives and three spoons would benefit my life, my mother would reply that one never knew when one might be required to eat inconspicuously at the White House.

My mother’s obsession with etiquette exceeded that of anyone else I knew and provided a tiny crack in her composure. During Sunday dinners, when children were allowed to join the adults—and no misdemeanor went uncorrected—one of my first rebellions was switching my fork into my left hand and my knife into my right, mashing potatoes and green peas onto the back of my fork and hoisting the load, British style, into my mouth, a maneuver my mother found intolerable. If, however, we happened to have British guests, she could say nothing until later, when I would argue the injustice of being forbidden to eat the very way her English mother had.

Until my twenties, when I joined the Peace Corps in Eastern Nigeria, I often ridiculed my mother for her insistence on table manners. At “home” in Michigan, the whole family found them a source of high entertainment. Even Mother had to smile at the extravagant sweeps of our soup spoons AWAY from us (never toward) and our insistence that everyone wait while we’d thoroughly chew and swallow a chunk of steak before speaking. My father, equally amused, frequently regaled us with gory descriptions of that day’s surgeries while we dug into plates of Chef Boyardee. “Ralph!” my mother would chide. “Ralph!” we’d mock as we begged for more.

Imperceptibly, despite kicking against the graces, I became them. Even as a young woman, I seemed to inspire in some of the people I encountered a reserve similar to that I had observed around my mother. Others, of course, dismissed my inherited need for civility—both my ex-husbands ignored my pleas for inaudible farting and unobservable mastication, ridiculing me exactly as I had my mother.

I have never eaten at the White House, nor has my mother—who has had tea with Eleanor Roosevelt—dined with the queen, but both of us have discovered that meticulous manners, though perhaps at first off-putting, curiously help bridge cultural differences and can earn one mysterious forgiveness for even the worst faux pas.

———————–

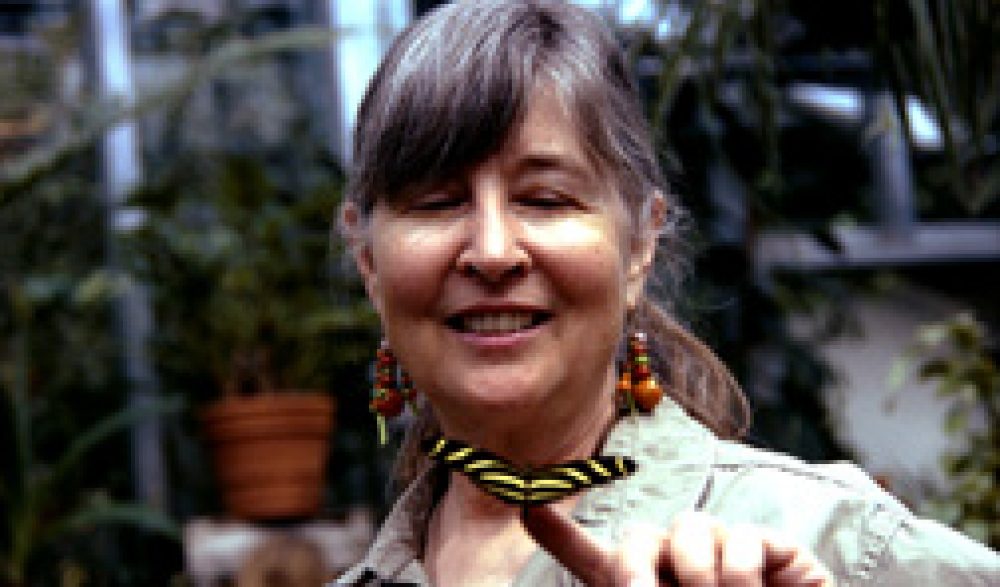

A WORKSHOP NOTE: I never put much value in my memories—like most people, I’d ask, who’d want to read about me? I’ve had a rougher version of these Pakistan pieces for almost twenty years and never shown them to anyone. They turn out to be a gift to my siblings, two of whom were too young to remember much and the other, my brother Dewey who is only a year and a half younger than me, an unexpected excursion into his own childhood. My mother, who clearly stars in my early life and has written her own memoir, at 97 is done with email and has not yet read these posts. When I’ve finished, I will print them out for her.

As to you who are actually reading all this—writing has always been a lonely art. Thank you for your welcome responses.